recently posted a note to aspiring songwriters via my Instagram account. It began simply, with these four words of advice: Finish what you start.

recently posted a note to aspiring songwriters via my Instagram account. It began simply, with these four words of advice: Finish what you start.

I then asked those reading my post to consider the classic songs we all know and love. (Take a moment to contemplate a few of your favorites.) What’s interesting, when you think about it, is that the great songs have little in common. Some are written alone, some collaboratively; some feature personal themes, some universal; some are built simply, some are labyrinthine. There is, however, one trait that all of these songs share in common: They’re finished.

If you’re a songwriter and you find yourself stockpiling unfinished verses and abandoned choruses, this article is for you. It’s chock-full of lessons that I’ve learned along the way, and you’ll hear from esteemed writers like Theo Katzman (Vuflpeck) and and James Valentine (Maroon 5) as well.

I hope this article will help you overcome whatever’s keeping you from finishing your songs. From my own experience, I can tell you this: By continually practicing putting the pieces together, and by being honest with yourself throughout the process, you’ll become a stronger and more nuanced writer as your songs get done, one by one. So, if you’re ready to roll up your sleeves and get some real work done, read on.

I hope this article will help you overcome whatever’s keeping you from finishing your songs. From my own experience, I can tell you this: By continually practicing putting the pieces together, and by being honest with yourself throughout the process, you’ll become a stronger and more nuanced writer as your songs get done, one by one. So, if you’re ready to roll up your sleeves and get some real work done, read on.

Beginner’s Mind

As a songwriter, I was a late bloomer. I didn’t really start writing until my mid 30s. (On a dare from Norah Jones, with whom I was touring at the time.) By then, I’d already been playing guitar professionally for 15 years. That gave me some advantages. I had learned to play hundreds of songs, in a wide array of genres, so I had a good understanding what songs were made of—musically, at least. The one thing I hadn’t paid much attention to before was lyrics. I was like a guy who’d regularly been hitting the gym for his upper body, but completely ignored his legs. When the light bulb finally popped on and lyrics were suddenly all I cared about, I had a whole lot of catching up to do.

My first step was to ask the best songwriters I knew to recommend some of their favorite lyricists. My writerly friends suggested Bob Dylan, Lucinda Williams, Tom Waits, John Prine, and others. In the timeframe I’m talking about—around 2003—Google wasn’t yet what it is today. Still, one could easily look up Dylan’s lyrics on the internet, and I did. Reading the work of the Old Masters, if you will, was so helpful. Yet I soon discovered that I learned much more by transcribing the lyrics myself. The two-fold act—listening intently and then writing each word longhand, in a notebook—helped me really get the lyrics on a deeper level.

If you’re not doing this sort of work already, I’d highly recommend it. You could even make a daily practice of it, choosing one song per day and transcribing the entire lyric, top to bottom. In doing so, you may discover an unexpected word choice or odd turn of phrase that inspires you to think differently about the way you use language; you may find that one of your favorite lyrics has a lot more words—or a lot fewer—than you’d thought, which could lead you to put more (or less) into your own songs.

Harmony Central

Everyone’s songwriting pathway is unique, of course. Maybe you’ve already got loads of experience writing lyrics, but are stymied when it comes to crafting compelling chord progressions. If that’s where you’re at, I’d recommend doing similar sort of work. As a daily practice—or as regularly as you can—transcribe chord charts for all sorts of songs. Once you’re sure you’ve made an accurate chordal roadmap of a song, the next step is to analyze its sections (intro, verse, chorus, and so on) individually. Which chord does each section start on, and where does it go from there? Is the harmonic progression a typical one (like I–V–vi–IV), or something more surprising? After breaking down each section, look at how the pieces fit together. If, say, the chorus is immediately followed by a verse, look at how these two sections connect, harmonically. How does the end of the chorus set up the beginning of the verse?

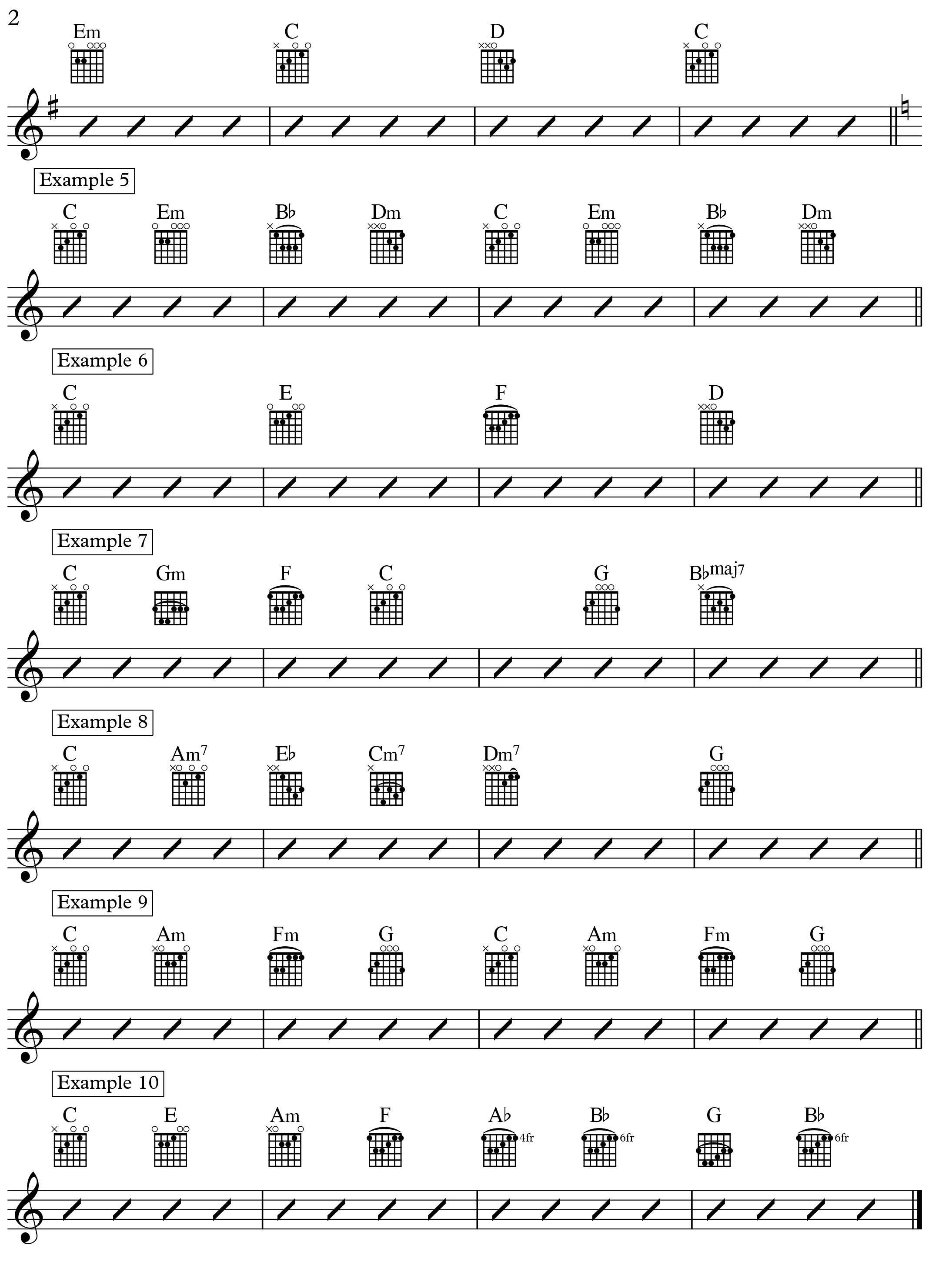

By way of example, let’s examine Bruce Springsteen’s song “The River.” Example 1 is modeled after the song’s intro. It’s an eight-measure phrase that starts on Em, then moves quickly to G (the home-base chord in this key). After a couple of other simple moves, the progression ends with two measures of C. Ending on C, and hanging there for a moment, keeps the mood open. It’s a great setup for the first verse, which begins on Em.

The verse section (Example 2) is also eight measures long, comprising two nearly identical four-measure phrases. The subtle difference between the two halves is worth noting. Em–G–D–C feels like an unanswered question, because it ends on C. Em–G–C–G is more complete, because it ends on G. That G dovetails nicely into the pre-chorus (Example 3), which starts on the C chord. What’s most interesting about the pre-chorus is that the chordal pacing (also known as the harmonic rhythm) slows down. In this song’s other sections, the chords generally change once per measure. Here, Springsteen sits on C and Am for two measures each. This downshift makes the chorus (Example 4). which follows, feel more urgent and kinetic, as it returns to the faster one-chord-per-measure clip.

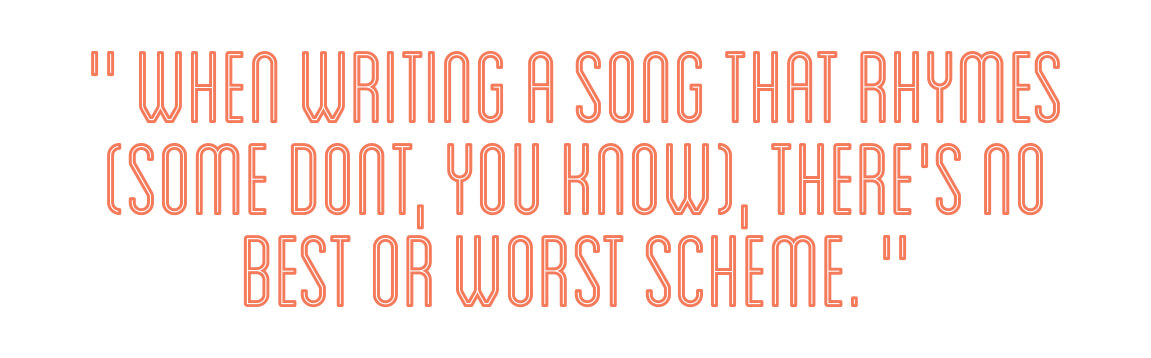

“The River” is just under five minutes long. Here’s how it breaks down.

Organized Rhyme

Let’s now return our focus to words. Earlier, I encouraged you to learn by transcribing the lyrics of writers you enjoy and admire—looking for inspiration in their word choices or phraseology. While that’s a great way to develop your lyric-writing skills, it’s not the only way. Another is by experimenting with rhyme and meter.

Look at the first stanza to the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” The rhymed words are found at the end of lines 2 and 4 (snow / go), while lines 1 and 3 do not rhyme. So the rhyme scheme here is ABCB.

Mary had a little lamb

Its fleece was white as snow

And everywhere that Mary went

The lamb was sure to go

“Humpty Dumpty,” on the other hand, follows an AABB scheme. “Little Jack Horner” is AABCCB. I’m using these childish examples because they’re commonly known. You absolutely should, of course, study the schemes of grown-up rhymes too.

When writing a song that rhymes (some don’t, you know), there’s no best or worst scheme. The important thing to be mindful of, as you craft more and more songs, is just how frequently you rely on the same formula. If the last five songs you wrote have AABB verses, challenge yourself to do something different next time. Even within a single song, each section type (verses, choruses, and so on) may be molded differently. Study the rhyming schemes of a few song verses that you love, then write several original verses, using the same constructions.

You should keep track of the meters and forms that you use frequently, as well. (In lyrics, as in poetry, the number of lines in a verse—and the number of syllables per line—is the meter.) As with rhymes, there’s no be-all-end-all meter that you should use all the time. The work to be done in this area—as you may have guessed—is to study the forms of some of your favored songs and then write a handful of songs in those same forms. Practice each form until you feel you can write creatively and juicily within it.

Before wrapping up this passage on lyric writing, there’s one more thing I need to mention: Take your lyrics seriously, but not too seriously. While fellow writers may appreciate keen wordplay and unorthodox rhymes, the average listener is more interested hearing a good story, well told. What’s more, many listeners don’t take the lyrics literally at all. Instead, they’re tuned in to the sound and shape of the words. In his book Life, Rolling Stones guitarist/songwriter Keith Richards talks about the importance of this, in terms of “vowel movement.” Richards ssserts that using the right sounds at the right time (or not) can make (or break) a song. What is “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” actually about? Does it matter?

The Toppermost of the Poppermost

You may have noticed that I haven’t said much about melody yet. That’s because of the way I typically work in my songwriting process. I’ll usually finish a lyric first—without a melody or a chord progression. What I’m going for at that point is a clear storyline, told with conversational language and colorful imagery, adhering to whichever meter and rhyme schemes I’ve chosen. Once I’m happy with my lyric, I’ll read it out loud—listening for inherent rises and falls in the words, as well as natural phrase lengths and breaks. This, for me, is where the melody begins to form.

Many writers, on the other hand, prefer to start with melody—perhaps using meaningless syllables like la-da-dee, or place-holder lyrics. (The Beatles’ “Yesterday” began as “Scrambled Eggs.” Paul McCartney worked on the song for months, apparently, before completing the now-famous lyrics.) Some write melodies a cappella, with no particular backing chords in mind. Others may build a progression or riff, then sing over the top of it, improvising wordless vocal melodies. They’ll record their improv, then listen—searching for anything that sounds like a particular word or cohesive phrase. Once there are some strong anchors in place, the rest of the lyric can be constructed around those.

If you’re curious to know how some of the legends do it (words first? music?), check out Paul Zollo’s book Songwriters on Songwriting. In it, Zollo talks process with Bob Dylan, Patti Smith, Tom Petty, and other powerhouse writers. Their insights may inspire you to come at the craft from some different angles. Over time, you’ll find one or two approaches that reliably help you move forward—turning your glimmering ideas into fully formed, ready-to-record songs. At the end of the day, that remains the goal. Finish what you start.

A Pro’s Perspective

Q&A with Vuflpeck’s Theo Katzman

Theo Katzman wears many hats in the soul/funk band Vulfpeck. Drummer, guitarist, singer, songwriter—whatever the song needs, Katzman brings it. He also releases his own original music. Heartbreak Hits is his latest full-length album.

How do you use the guitar in your songwriting process?

Occasionally, I’ll be playing guitar and an idea will come up. A lot of times, though, instruments have nothing to do with the writing. I’ll work to get the core of an idea, then use the guitar or the piano to accompany it.

I usually start with a lyric and a melody. It could be just words and rhythm while I’m fleshing out the lyrics. Sometimes that leads me into a funny position where I have two verses, each with their own pre-chorus, and then a chorus—and yet I have no actual music. I’ve been working on something like that this week. I think it’s a cool song, except it’s not really a song yet. I still need to find the notes, melodically.

Which song do you wish you’d written?

If I have to choose just one, I’ll say “Lakes of Pontchartrain”—an American folk song recorded by Irish singer Paul Brady. That song kills me. It’s about a guy who sets out on his own. He meets this girl who’s super kind to him, even though he’s a stranger. He falls in love with her and asks her to marry him, but it’s not meant to be. She has a man who is away, at sea, and she’s waiting for him to return. So the guy leaves, but he never forgets her. In the last verse, he sings:

So fare thee well, me bonny young girl, I never may see ye more

But I’ll ne’er forget your kindness in the cottage by the shore

And at each social gathering, a flowing glass I’ll drain

And drink a health to me Creole girl by the Lakes of Pontchartrain

It’s a beautiful way to say, basically, “I had this moment with someone, and that’s all. But damn, that was cool.”

Which of your own songs are you most proud of?

“Good to Be Alone,” from Heartbreak Hits. There’s a little sarcasm in the title—like, is it really good to be alone? But it’s not a sarcastic song. It’s a country song, with just three chords. I’m proud of it because it feels kind of classic and universal, but I also discovered a unique way to say what I wanted to say.

A Pro’s Perspective

Q&A with Maroon 5’s James Valentine

Guitarist/songwriter James Valentine is a founding member of the socko pop/rock band Maroon 5.

How do you use the guitar in your songwriting process?

Guitar was central for the first part of my career. Songs like “She Will Be Loved,” “Never See Your Face Again,” and “Wake Up Call” all started with guitar riffs. Later on, during the making of our fourth record, I got into experimenting with programming beats and using synthesizers, which was a refreshing change. I’m more limited as a keyboard player, but sometimes those limitations inspire me to write differently. “Sad” was written on piano. It never would have come to me that way on guitar.

Lately, I’ve been gravitating back towards the guitar as starting point. When I go to songwriting sessions, I like to start with just an acoustic. It’s crazy, but that often seems very novel to songwriters who are used to writing to tracks or beats. I think it’s good to change up your process to keep things fresh, no matter what your instrument is.

Which song do you wish you’d written?

Any Steely Dan song—especially “Any Major Dude” or “Deacon Blues.” These are perfect songs, to me. Lyrically, Steely Dan’s songs have a sense of humor, while still being emotionally heavy. I think that’s hard to do. Musically, they’re just insanely brilliant—but everyone knows that.

Which of your own songs are you most proud of?

“She Will Be Loved” will always be a really special song to me. It opened up a lot of doors for us early on in our career. It’s surreal to see how the song has become a part of the soundtrack of people’s lives. I hear it’s played at weddings and proms. I love that!

A Pro’s Perspective

Q&A with Mike Viola

Producer/musician/songwriter Mike Viola is best known for his work with Ryan Adams, Jenny Lewis, and Fall Out Boy. If his name isn’t familiar to you, his songs most likely are. You may have heard them in the films That Thing You Do! or Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story.

What’s something you learned about songwriting in the past year, that you wish you learned sooner?

I learned that my first idea is likely the most authentic, the closest to the inspiration. So, when the song starts to happen, you have to abandon reality right away in order to capture its authenticity, and keep writing till your hand cramps up. I still use notebooks. I like to see the trail behind me and the blank pages ahead. I like to feel the rip in my wrists, rather than in my eyes from looking at a screen.

Big lesson, that one. Dan Bern taught me that without telling me, just by doing, by his insistence on using the crazy shit we came up with while driving around in his car, writing together—never changing it. That’s our only chance to access the subconscious without a heavy does of psychedelics or writing in your sleep.

A Pro’s Perspective

Q&A with Lisa Loeb

Lisa Loeb is a singer-songwriter, producer, touring artist, author and philanthropist who started her career with the platinum-selling Number 1 hit song “Stay (I Missed You)” from the film Reality Bites.

What’s something you learned about songwriting in the past year, that you wish you learned sooner?

I wish I knew that collaborating was as fun and easy as it is. It took me a while to figure out that you have to find the right partners and collaborators with the right energy and work styles.

Harmony 2.0

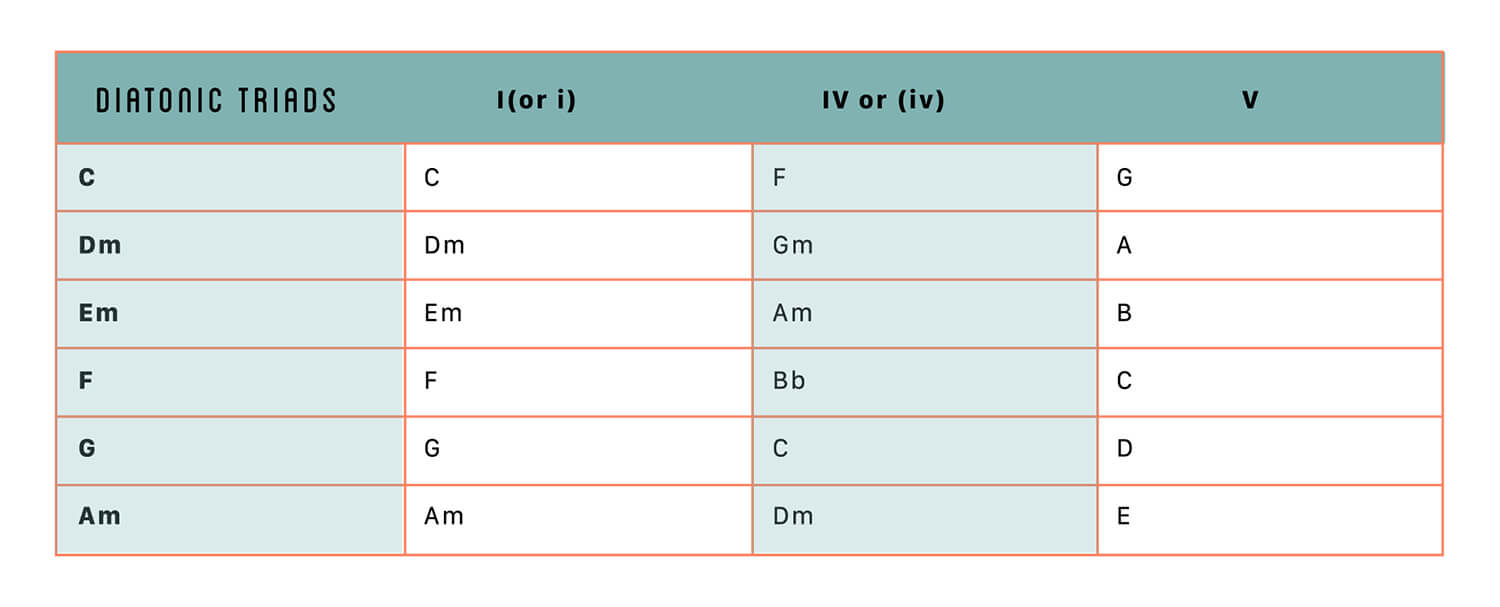

For those of you who already have a solid grasp of chord-movement basics and are looking for ways to write more colorful progressions, here are a couple of concepts that will expand your palette. The first idea is relatively simple, using diatonic harmony and the close relationships between I, IV, and V. In the key of C major, for example, the native triads are C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am, and Bº. The most cogent progressions we can make from these seven chords would include just C (I), F (IV), and G (V). Countless classic songs—in so many genres—have been written using just these fundamental harmonies. Now, watch what happens if we consider each of the diatonic triads as a I—or i, for minor triads. (We’ll discard Bº, because diminished harmonies are generally used as passing chords, not as temporary tonal centers.) Then we can use its IV and V as well, keeping these guidelines in mind: For major triads, the IV and V will also be major; for minor triads, the iv will be minor and the V will be major. This introduces some new chords, as you’ll see in the table, below.

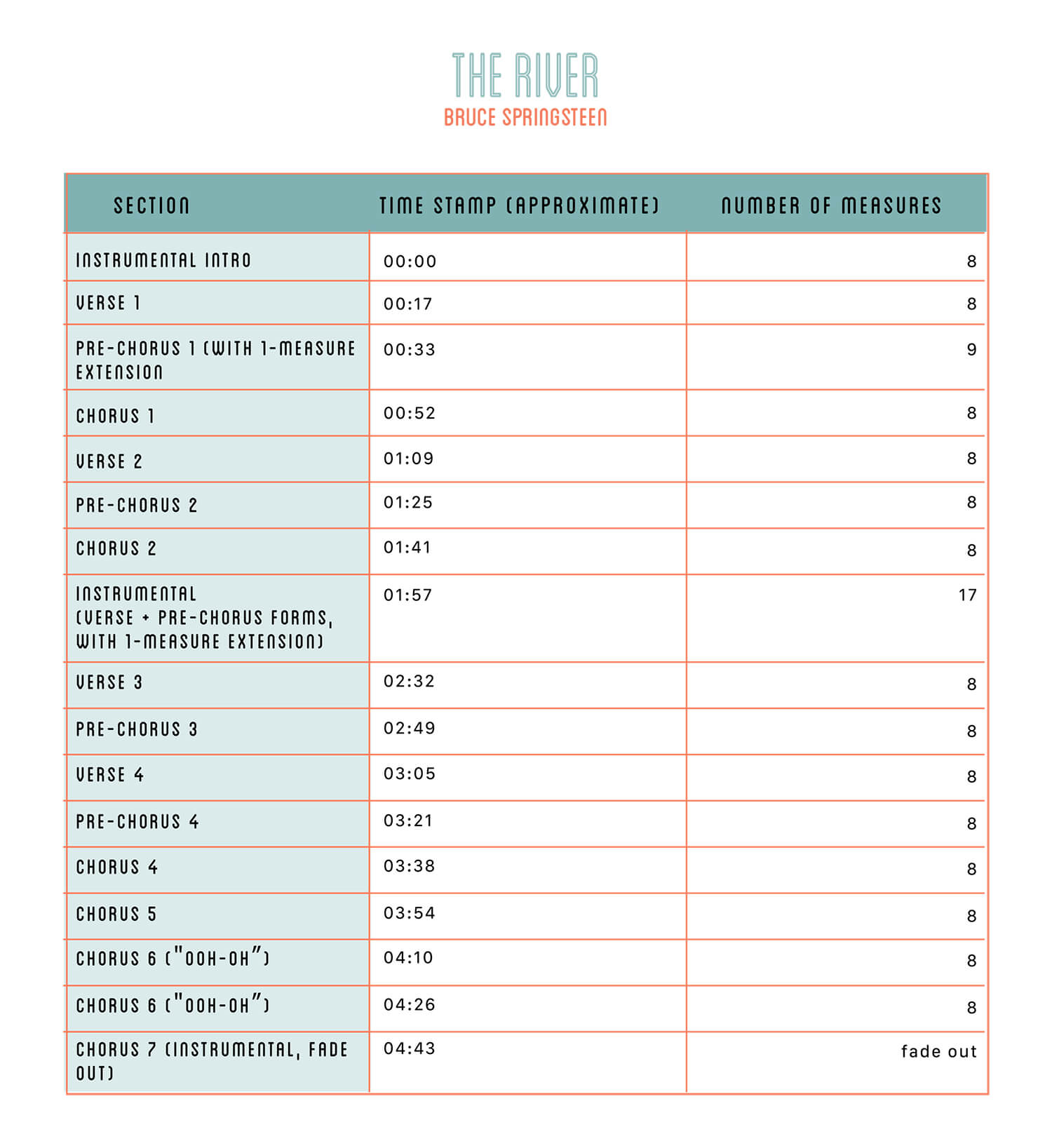

As you may have noticed, there is some redundancy. For instance, G’s IV chord is C—a chord we already have in the key of C. But there are six fresh sounds here: D, E, Gm, A, Bb, B, and B. That lets us build progressions like Example 5 (similar to Bob Dylan’s “Lay Lady Lay”), or Example 6 (like to Otis Redding’s “Dock of the Bay”), or Example 7 (similar to James Taylor’s “Fire and Rain”). Next time you’re writing a song, and feeling bored with the same-old-same-old chord changes, try folding one or two of these chords into your verse or chorus. (If you’re writing in a key other than C, you’ll have to transpose this table.)

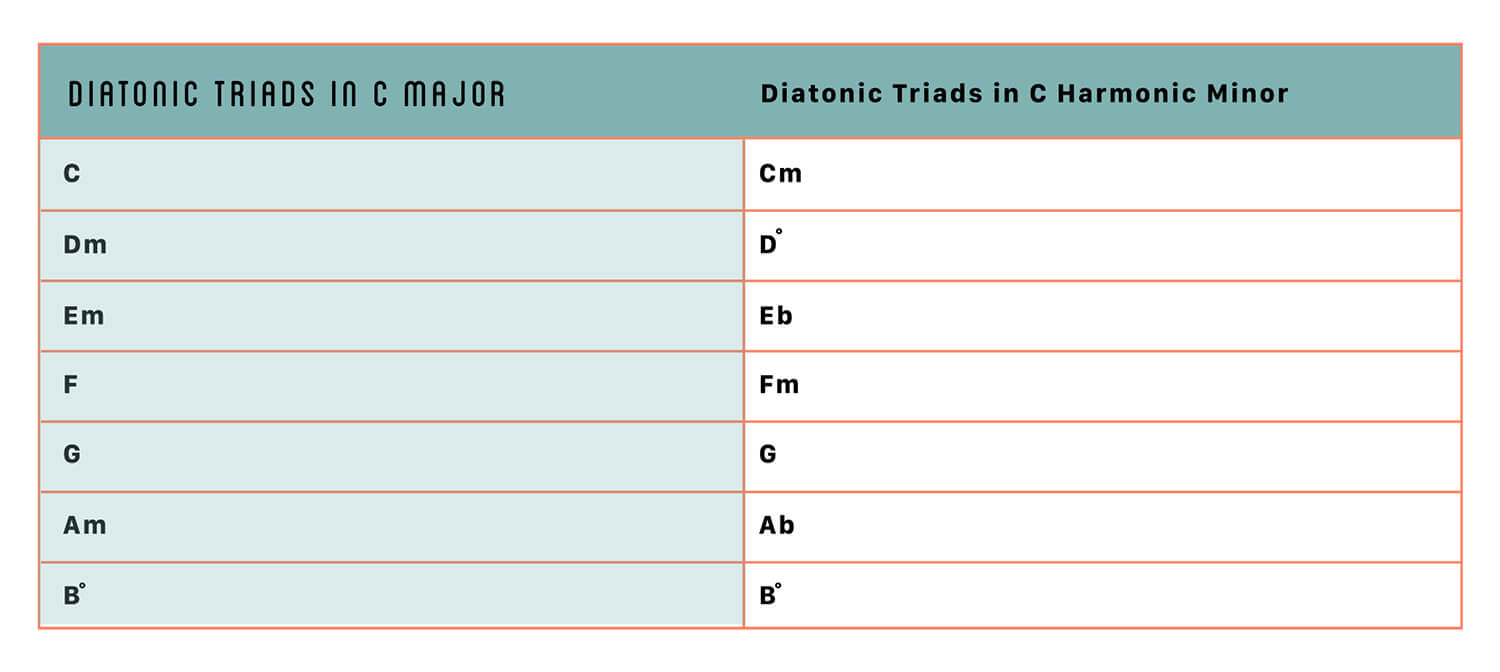

The next concept is similar, but uses parallel key centers. C major and C minor, for example, are parallel key centers. (This is not to be confused with relative key centers—like C major and A minor, which share the same key signature.) Check out the table, below, comparing the native triads from the C major scale and the C harmonic minor scale.

As before, we’ll discard the diminished triads. The useable new sounds here are Cm, Eb, Fm, and Ab. These can be used to build progressions such as Example 8 (similar to the Beach Boys “Warmth of the Sun”) and Example 9 (like Santo & Johnny’s “Sleep Walk”). Things get really interesting when both sets of new chords (from the I-IV-V axis as well as the parallel minor key) are utilized. That’s where Example 10’s twisted progression (à la Nirvana’s “Lithium”) comes from.