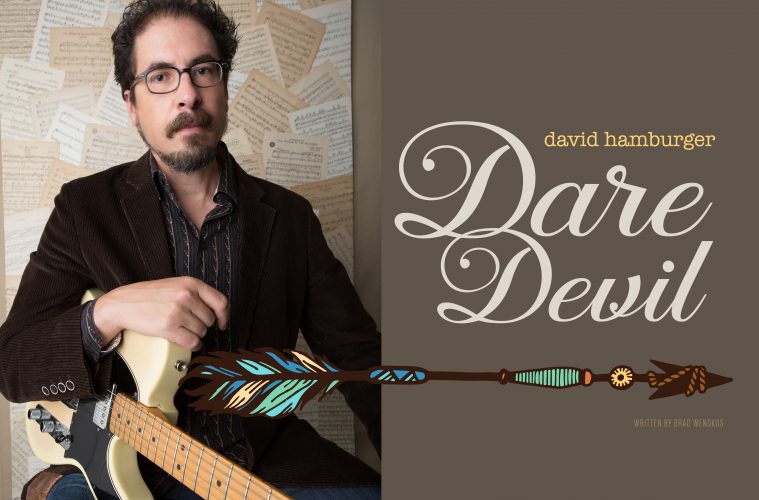

David Hamburger was the very first artist who dared to collaborate with us back in the day when instructional books, audio CDs, and DVDs ruled the music education world. TrueFire was just a peanut of a company and our new-fangled approach for teaching folks how to play guitar with interactive video technologies was untested and unproven. That took some guts for someone who was already immensely successful authoring best-selling, award-winning instructional books and DVDs.

I remember being nervous about that first session. I was such a big fan of David’s work and wanted everything to go as smoothly and professionally as possible. Naturally, everything that could go wrong, went wrong. Murphy brought the entire family to those first sessions.

You have to first picture the studio we were working in to fully appreciate what must have been running through David’s mind when he first saw it. Located in a dark and dank mezzanine of the old building we were working in at the time, the “studio” was a small 12×20 foot office space with short 7’ ceilings, no sound-proofing, no acoustical treatments whatsoever, no control room, inadequate and very loud AC that we had to turn off while recording, hot oversized lights, jerry-rigged video cameras, cheap audio mixers, and a big old leather coach crammed up against one wall with an old school blackboard hanging from another.

If David flinched at first sight, I sure didn’t see it. And he didn’t flinch when the bulbs blew out multiple times mid-take. Nor did he flinch when the cameras stopped working properly, or when we had to stop to cool the room down to a manageable 90 degrees, or when one of us (OK, me!) tripped over the audio cables, which then had to be replaced, and so on and so on. Everything that could go wrong, went wrong. With one exception — David’s presentation of the material and his performances of the examples were flawless. Absolutely flawless.

We produced Slide Shop that very first session, and then Blues Alchemy, New School Fingerstyle, Fingerstyle Handbook, and Blues Architect in following sessions, all of them in that same studio. Never once did he bitch, moan, or complain. To this day, every one of those first generation courses represent what I consider to be amongst our best work educationally speaking. David raised the bar even further with the five additional courses that he produced with us more recently, in our current studios.

David and I bonded in many ways over those sessions. Professionally, we got to the point where we could finish each other’s sentences when it came to planning a new course or new teaching approach. I also learned volumes from David about artists’ perspectives, expectations, and sensitivities. These lessons helped me shape the very backbone of our artist relations mandates. Personally, I’m proud to call him a good friend and I always enjoy his company and conversation.

David also dared to establish a career as a composer for film, television and advertising from scratch, all while making a living as a musician, having babies, and growing a family. Despite how near impossible a challenge that could be, I never had a doubt that he would be successful. Sure enough he was and still is.

His most recent work includes scoring the CNN documentary series High Profits. His music is featured in two ongoing series on A&E, Shipping Wars and My 600 Pound Life, and his score for the film, When I Rise, debuted at SXSW and has aired multiple times on PBS’ Independent Lens.

David is one of the most extraordinarily talented, driven, creative, and single-mindedly determined people that I have the pleasure of knowing and working with. You can get to know him better too by reading his answers to our Proust-like interview.

Dig in!

![]()

What is it about the guitar that attracted you to it originally, and still fascinates you today?

I came from summer camp wanting to play clawhammer banjo, and then, within the space of week, my sister played me “Sgt Pepper” and my parents borrowed a 3/4 Harmony guitar from a neighbor. Turns out you can play Beatles songs on the guitar, so that was a big part of the attraction, I guess. Plus it has frets – I’d been playing the violin since I was 8, and the guitar just made more sense from the very beginning. I liked the way it felt, to hold it and to play it.

It seems like there’s always something to learn, and there’s guitar in just about every kind of music I love. I’ve gone through phases where it wasn’t my favorite thing – I got obsessed with playing bluegrass Dobro and honky tonk pedal steel in my 20s, and the guitar was just a utilitarian thing for a time – I taught lessons, and wrote songs on it, but wasn’t working on getting better at it. Right now, I’m kind of consumed with it again.

I started playing electric guitar on my gigs again about a year ago, and I’ve never been more into thinking about what you can do with it and how it can sound. For the longest time, I’ve skated by in terms of gear when it comes to electric guitar. I still have one of those grey plastic Boss pedal cases in the closest, but I finally replaced it with a bunch of boutique gizmos, and I have this small hollow body Gibson that I’m totally into. It reminds me of how I felt when I began to play the Dobro – like the quest is on to figure out how to play as well as possible, to dress away everything that isn’t me and amplify everything that could be.

That process – figuring out who you are as a musician – that’s the fascinating thing, for sure. And I think it took me a long time to have enough internal gravity to even say, “Yes – that is the point. That’s what I’m doing here, being an artist, with a set of criteria and a point of view.”

Whether living or dead, who would you like to have dinner with?

I’ve met a few of my heroes, and wound up wishing I hadn’t, so it’s hard to say. I’ll go with Garry Trudeau, the guy who writes Doonesbury. I saw him give a commencement speech at Vassar and it was pretty great.

Name three things a player can do to improve their musicianship.

Listen to the music you’re trying to play, transcribe it in small doses, and practice improvising to a metronome.

If not yourself, who would you be?

Musically? Ry Cooder, Ray Bryant or Mose Allison. Or Theodore Shapiro, the guy who did the score to the film State and Main (and St. Vincent). Although my paternal grandfather, Ed Hamburger, was pretty rad – I wouldn’t have minded being him, either.

Given the changing business landscape of the music business and how tough it is to sell records etc. — What are the positives about the current evolution of the music business?

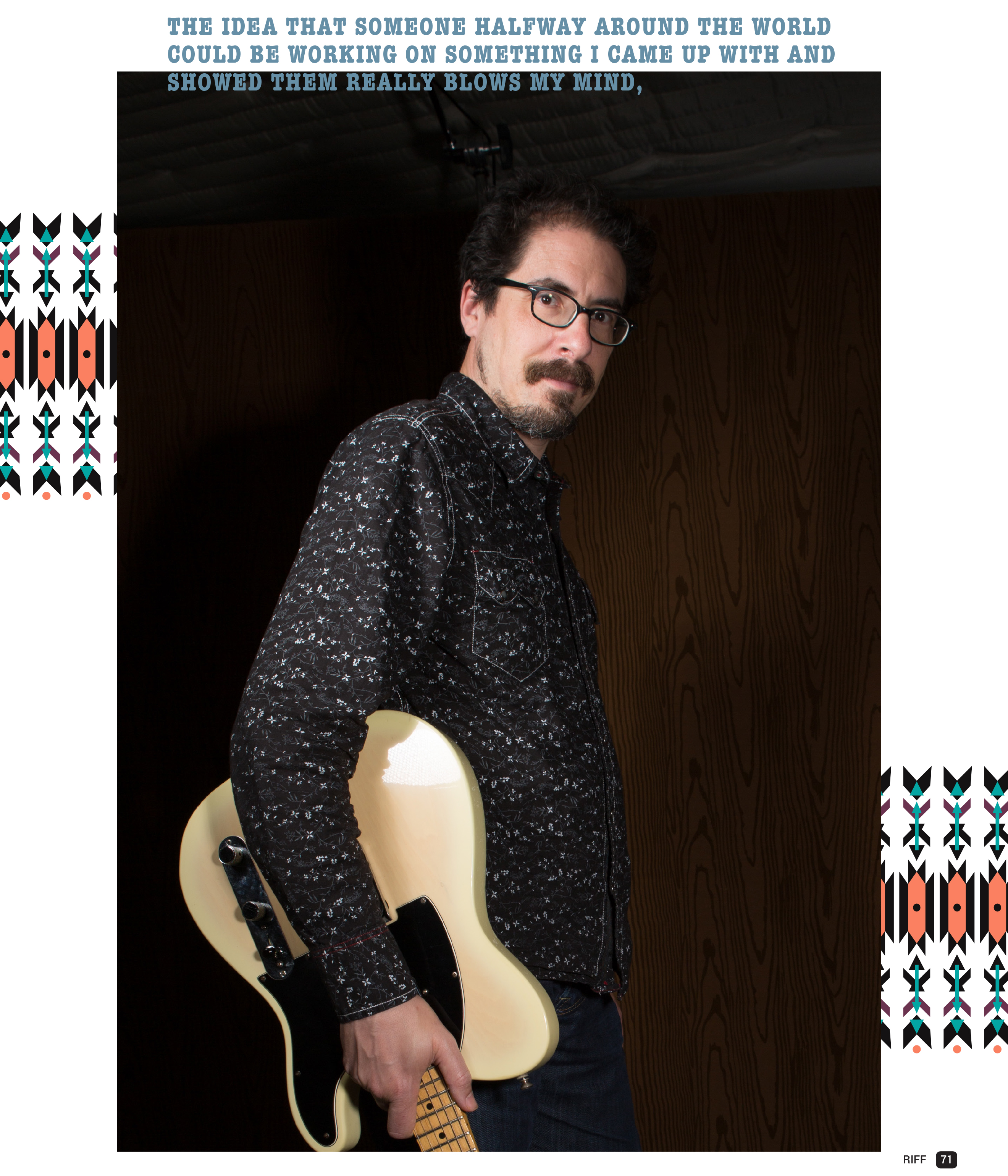

You can reach a lot a people beyond your immediate vicinity. I’ve gotten emails about my TrueFire courses, and my books, from Iran, New Zealand, France – that’s kind of amazing. The idea that someone halfway around the world could be working on something I came up with and showed them really blows my mind, and is good to remember on those days when I feel like I’m completely spinning my wheels.

Your favorite motto?

“If you’re going to do it, do it right.” I grew up hearing my father say this, and he probably got it from my grandfather, because that sounds like the kind of thing my grandfather would say. When I think about it consciously, it doesn’t really sound like me, but I know it’s ingrained in my DNA, for better or worse. It definitely affects the way I make a sandwich; just ask my wife.

What do you dream about? Literally.

Playing a wind instrument. Trumpet, clarinet, trombone, you name it. It’s like those dreams where you dream you’re breathing underwater. You know it’s impossible, but it’s happening anyway.

What are your aspirations?

Time to make records, an audience for my work, and money in the bank. How honest do you want these answers to be?

What one event in music history would you have loved to have experienced in person?

Being at Abbey Road while the Beatles were making Rubber Soul, being in the audience for Live at the Regal or the Allman Brothers’ At Fillmore East, or watching Ry Cooder make Paradise and Lunch.

Your favorite heroes in fiction?

Jeeves. Archie, from the Nero Wolfe stories. Hobbes, from the comic strip. I guess I have a weakness for seconds-in-command who are good with a riposte.

What or who is the greatest love of your life?

Learning things.

Your favorite food and drink?

Real pizza, and Mexican lager. Seriously, what do I have to do to make this whole craft ales thing go away?

In your next life, what or who would you like to come back as and why?

I’m pretty down with who I got to be this time around.

The natural talent you’d like to be gifted with (other than music)?

Fixing things. Cars, in particular. And building things. I know, that’s two things, but they’re related. My family thinks I actually can fix things, but I’m talking about projects that involve more than Krazy Glue or a screwdriver.

In life or in music, what is the one central key learning that you’d like to pass on to others?

Improvement seems to be about proximity – if you hang around near the things you want to get better at, it slowly begins to happen. It helps if you can clarify just what it is about the thing you’re hanging around that interests you. For instance, I dropped out of a graduate jazz program almost thirty years ago, but when I realized all I’d ever really been interested in was how to play the changes on the blues, that gradually began coming into focus. It still took time, and I’m still sorting it out, but it helped to begin by carving away everything that didn’t look like an elephant in the first place. That focus really matters, because like most people, I don’t have a ton of time to practice, and anyway, I never had the patience to practice much, so I had to figure out how to get better in the half an hour or forty-five minutes I might manage to shoehorn into the day.